Greetings! It’s Cocktail Hour at the Intentional Table!

** Usually, I publish this on Fridays… at about, oh, let’s say, 5:00PM (PST), around Happy Hour, so we are back on schedule! **

Wine Through the Ages: A Heritage at Risk

As a winemaker myself, this is a hard topic to get through my thick head. Ugh.

The story of wine stretches nearly 9,000 years, making it one of humanity’s oldest and most treasured achievements. From the chance fermentation of wild grapes to the sophisticated viticulture we know today, wine has shaped commerce, religion, art, and social gatherings for millennia. Yet despite its remarkable resilience, wine now faces profound challenges.

Climate change, shrinking biodiversity, and rapidly shifting consumer preferences threaten the delicate foundations that have sustained vineyards for countless generations. By understanding wine’s ancient history and its current vulnerabilities, we can better grasp why preserving this heritage matters for our shared future.

Maybe. I am not entirely certain that people will think that this matters. That wine matters; it was cool, but it’s had its day. There is something so sublime about how wine mirrors nature in all its beauty and finesse. It could be as lost as your child’s attention at the dinner table.

Accidental Discovery and Early Innovations

Before formal agriculture took hold, nomadic hunter-gatherers likely discovered wine when wild grapes were left in containers and accidentally crushed. Natural yeast on the skins fermented the juice, transforming the fruit into a mildly intoxicating liquid.

Enthralled by its uplifting effect, aka drunk buddy (lol), these early communities pressed grapes deliberately to reproduce the phenomenon. They also developed tools such as woven baskets and later clay vessels to ferment and store the juice, indicating a growing appreciation for the sauce!

Some scientists trace our love of alcohol back to the days when primates sought fermented fruit, which was higher in calories and easier to detect from a distance.

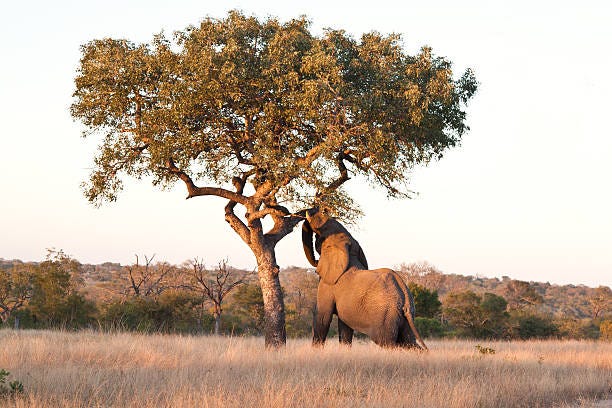

I have witnessed this in South Africa. Have you ever heard the phrase “Drunk as a Monkey?” Well, the Marula Tree makes this fruit that is “kinda-guava-like.”

Here is our friend, eating some marula fruit that has dropped to the ground and has spoiled, aka fermented.

… and here she is a bit later with a bit of a reduced risk tolerance and a luxurious thought or two about the chimp at the end of the bar…. 😎

This evolutionary trait may have primed humans to embrace wine once they encountered wild Eurasian grapevines after migrating from Africa. By around 6000–5000 BCE, people in regions like the South Caucasus deliberately cultivated vines and improved techniques, leaving clear traces in the form of decorated pottery and residual wine compounds.

Hey, it could be worse. Let’s say you have some of these guys:

Same thing. They eat the fermented fruit and get well…

The problem is that not all of them are happy, sleepy drunks. Sometimes, they decide it’s time to run through a village and make a little mayhem. Nobody wins this one.

Archaeologists studying sites in modern-day Georgia and Iran uncovered evidence of grape seeds, wine residues, and tree resin used as a preservative. These discoveries show that Stone Age farmers had mastered fermentation and storage methods, illustrating how crucial wine became to emerging agricultural societies. With the dawn of the Neolithic, communities recognized wine as a novelty and a cornerstone of social and economic life.

The resin is still used in Greece in a wine called Retsina. It’s very band-aide tasting and acidic, but really, really, and I mean really cold on a hot Greek beach, it works.

Ancient Civilizations and Their Enduring Contributions

Cultures like the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans transformed wine from a simple fermented drink into a refined art. Egyptians cultivated grapevines along the Nile’s fertile banks and recorded detailed harvest information, paving the way for an early understanding of vintages. Though red wine dominated due to its striking resemblance to blood and its sacred symbolism, discoveries within pharaohs’ tombs reveal they also produced white wine. Amphorae sealed with clay stoppers preserved wine for transport and ritual use, reflecting an advanced approach to winemaking.

Meanwhile, the Greeks democratized wine, making it widely accessible beyond religious rites or aristocratic banquets. Participants in the symposium—an iconic social gathering—mixed wine with water in communal vessels. This practice underscored wine’s role in fostering intellectual discourse, community bonds, and cultural values. Greek maritime trade routes carried this ethos throughout the Mediterranean, enriching diverse regions with vine cuttings and winemaking methods.

“Wine to me is passion. It’s family and friends. It’s warmth of heart and generosity of spirit.” — Robert Mondavi

The Romans built on Greek foundations, extending vineyards across Europe as their empire grew. They innovated using wooden barrels instead of clay amphorae and developed the arbustum system, where grapevines climbed living trees to maximize sunlight and ventilation. Roman legions ensured that vineyards took root in every new province, laying the groundwork for wine’s deep integration into European culture. Places like Gaul, Hispania, and the Rhine regions became new centers of production, forging local styles that endure today.

We still use metal trellises that mimic the tree.

Sacred Dimensions Across Religions

Over centuries, wine transcended its status as a mere beverage to become a sacred symbol in various religious traditions. Ancient Egyptians associated it with gods of fertility and the afterlife, while the Greeks revered Dionysus, whose festivals merged revelry with spiritual significance. In Roman mythology, Bacchus served a similar function, presiding over ecstatic rituals that embraced the intoxicating power of wine.

King Tut had jars of wine, laced with Blue Lotus Flowers (another post) in his tomb for the after - the - after life party. I am pretty sure Prince was there.

Within Christianity, wine gained special prominence through the story of the Last Supper, where Jesus offered wine as a symbol of his blood. This act elevated wine to a central place in Christian worship, formalizing its role in the Eucharist. Monasteries later became critical repositories of viticultural knowledge, carefully tending vines and experimenting with soils, climates, and grape varieties. The Benedictines and Cistercians, in particular, refined winemaking methods and meticulously documented their observations. In Burgundy, for instance, these monastic orders painstakingly mapped vineyards, noting the nuanced differences in soil and microclimate. Their work laid the foundation for the concept of terroir—a term that expresses how a wine’s character reflects the land and local conditions.

This fancy word is often used as a cudgel for those who ‘just don’t know or understand.’ This is a large problem that I will speak to below.

“A great wine is a reflection of its origin—the terroir, the climate, and the people who craft it.” — André Tchelistcheff

Spreading Vines Worldwide

During the Age of Exploration, Europeans carried vines to the Americas, Africa, and Australia, forever reshaping global wine production. Spanish missionaries introduced grapes throughout Latin America, primarily for sacramental needs, but local populations soon embraced winemaking for everyday use. In places like Chile and Argentina, transplanted vines thrived in new terrains, giving rise to traditions that merge Old World methods with local innovations.

Across North America, early colonists attempted to cultivate imported European varietals, though native grapes often proved more resilient. Over time, growers learned to adapt, eventually creating booming wine regions in California, Washington, and beyond. South Africa and Australia also developed their own distinctive vinicultural cultures, shaped by climate, geography, and waves of immigration.

But, all overproduced, monocropped agriculture must come to an end at some point. Introducing phylloxera.

Phylloxera’s Devastation

One of the most significant disruptions to wine’s global journey emerged in the 19th century when the microscopic pest phylloxera ravaged Europe’s vineyards. Accidentally introduced from North America, this root louse destroyed countless acres and threatened to annihilate Old World grape stocks. The crisis ended only when horticulturalists discovered that grafting European vines onto pest-resistant American rootstocks protected against the infestation.

Although this solution saved European wine, it also led to a dramatic narrowing of vine diversity, as many older varieties were abandoned in the rush to replant with more vigorous or commercially appealing clones. These events permanently reshaped the vinicultural landscape, catalyzing research into the genetic makeup of grapes and the importance of maintaining diverse grape varieties.

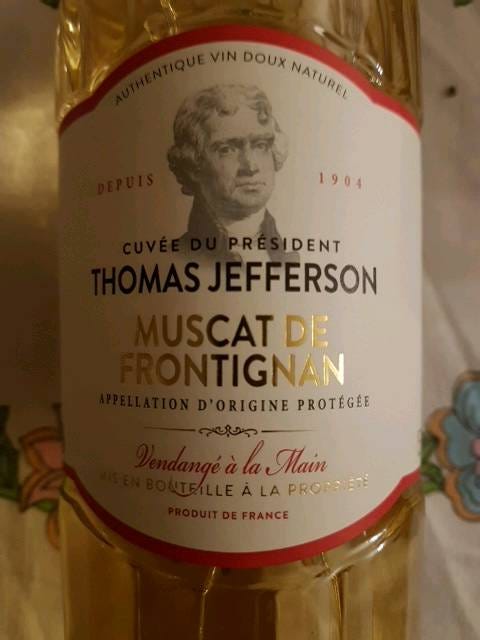

So, here is a short version: America (before it was) sent Thomas Jefferson to France as an ambassador. He gets really excited about French wine. (Of course.) Then he gets a ton of clippings and brings them back. He was trying to replicate this over here. It works, even though the species is not native to North America.

Oops, here comes phylloxera, which wipes out nearly all of France’s grapes. So, France calls up TJ on his iPhone and says, “Hey, buddy… still got those clippings?”

The US had to graft the vines to adapt to here, and guess what? Phylloxera resistant. Winner! So, TJ saves the wine industry in France by returning clones of what he took from there. I love that! I am glad that TJ has his ringer on when they called.

You KNOW that the French love this guy if he is on a French label. Really.

Challenges in a Rapidly Changing World

Today, wine faces a host of modern pressures. With rising temperatures, erratic weather patterns, and increasing water scarcity, climate change threatens areas historically ideal for grape cultivation. Regions in southern Europe, parts of California, and other famed wine-growing locales may become unsuitable for certain varietals in the coming decades. Warmer weather accelerates ripening, leading to higher sugar levels—and thus higher alcohol in finished wines—while drought and new pests introduce further uncertainty.

From my first-person perspective, every harvest in Sonoma is a dice game. When I started making wine here in 2016, you never knew what was going to happen.

“Wine is constant proof that God loves us and loves to see us happy.” — (Often attributed to Benjamin Franklin)

Biodiversity loss compounds these problems. Modern monoculture practices reduce the natural buffers that help vineyards resist pests and diseases. Traditional vineyards once contained diverse landscapes that fostered beneficial insects and robust soil life. As the industry grows, the pressure to plant high-yielding varieties intensifies, overshadowing lesser-known grapes that might hold genetic keys to future resilience. Erosion, water contamination, and chemical inputs further erode delicate ecosystems.

Economic pressures also loom large. Labor, glass, corks, and transportation costs have climbed while inflation has squeezed profit margins. Look back a couple of posts and see what I have to say about labor, love, culture, and the prevailing cost. It’s not going to work out well.

Consumers’ shifting tastes add another layer of complexity. Younger buyers often look for lower-alcohol or sustainably produced wines or switch to craft beers and non-alcoholic beverages. This evolving marketplace forces producers to innovate while retaining the character and identity that have defined their wines for generations. Some wineries now embrace the “sober curiosity” movement by offering sophisticated zero-proof options or working to reduce alcohol levels without losing flavor depth. Even traditional wine enthusiasts are exploring these alternatives, pushing the industry to adapt while maintaining its enduring appeal.

Preserving a Living Heritage

With a legacy spanning millennia, wine represents far more than a commodity; it’s a cultural touchstone connecting us to our ancestors and one another. Scientists and growers collaborate to develop climate-resilient grape varieties and sustainable cultivation methods. Techniques like dry farming (as in ALL of Italy), canopy management, and precision irrigation help vintners adapt to warmer conditions without sacrificing quality. Organic and biodynamic movements ( I use only these practices) are gaining traction, aiming to rebuild soil health and encourage ecological balance within vineyards.

“In wine, there’s truth, and we owe it to ourselves to protect that legacy.” — Anonymous old-world vintner

Many growers also rediscover heritage grape varieties, which can offer natural resistance to harsh conditions. Reviving neglected vines preserves historical flavors and broadens the genetic base crucial for facing environmental challenges. In regions from Italy to Portugal, local grapes are finding a new audience among winemakers who value authenticity over mass-market appeal.

Government policies that reward sustainable farming, along with investments in water conservation and pest management, can also safeguard the future of wine. For example, some European nations provide financial incentives to maintain traditional terraces and support small-scale producers. Such measures protect biodiversity and retain the cultural landscapes that have defined winemaking regions for centuries. I cannot say that we support that well here in the US now.

A Legacy Worth Saving

From its accidental origins to its global expansion, wine has evolved alongside humanity, bearing witness to revolutions, explorations, and transformative cultural shifts. It has been a symbol of fertility, a medium of commerce, and a spiritual emblem. Protecting this rich tapestry requires mindful steps to reduce carbon emissions, preserve biodiversity, and uphold sustainable practices. If we act decisively, wine’s next chapter can be one of renewal and rediscovery, where ancestral wisdom meets modern science to carry on a legacy like no other.

“Making good wine is a skill. Fine wine is an art.” — Robert Mondavi

Through centuries of adversity—be it invading armies, devastating plagues, or the phylloxera scourge—wine has demonstrated a unique resilience. Yet the challenges of climate change and shifting global demands pose an unprecedented threat. For wine lovers and novices alike, recognizing what is at stake is the first step toward preserving the landscapes and traditions that shaped this timeless drink. In doing so, we ensure that the simple, profound pleasure of sharing a bottle endures for generations, remaining as vibrant a reflection of human heritage as it has been for thousands of years.

I would love to wax poetic about this, but it’s Friday. Get out there and have a glass of wine if you are so inclined. It is so much more than it seems. If you do not imbibe, that’s fine, as there are alternatives. The Intentional Table is about tradition and consideration of all the bounty that nature hands us as gifts.

Blessing from this Intentional Table and its humble cook/ winemaker.

Cheers!